The Coral Here She Comes Again

Coral reefs are the most various of all marine ecosystems. They teem with life, with perhaps one-quarter of all ocean species depending on reefs for food and shelter. This is a remarkable statistic when you consider that reefs cover only a tiny fraction (less than ane percentage) of the earth's surface and less than two percent of the ocean bottom. Because they are so various, coral reefs are often called the rainforests of the sea.

Coral reefs are likewise very important to people. The value of coral reefs has been estimated at 30 billion U.S. dollars and perhaps as much as 172 billion U.Southward. dollars each twelvemonth, providing food, protection of shorelines, jobs based on tourism, and even medicines.

Unfortunately, people also pose the greatest threat to coral reefs. Overfishing and subversive fishing, pollution, warming, irresolute ocean chemistry, and invasive species are all taking a huge toll. In some places, reefs have been entirely destroyed, and in many places reefs today are a pale shadow of what they one time were.

What Are Corals?

Beast, Vegetable & Mineral

Corals are related to sea anemones, and they all share the same unproblematic structure, the polyp. The polyp is like a tin can open at merely one terminate: the open up finish has a rima oris surrounded by a ring of tentacles. The tentacles have stinging cells, called nematocysts, that allow the coral polyp to capture minor organisms that swim besides shut. Inside the body of the polyp are digestive and reproductive tissues. Corals differ from ocean anemones in their production of a mineral skeleton.

Shallow water corals that live in warm water often have some other source of food, the zooxanthellae (pronounced zo-o-zan-THELL-ee). These single-celled algae photosynthesize and laissez passer some of the food they make from the sun'southward energy to their hosts, and in exchange the coral animal gives nutrients to the algae. It is this relationship that allows shallow h2o corals to abound fast plenty to build the enormous structures we call reefs. The zooxanthellae also provide much of the green, brown, and reddish colors that corals accept. The less common majestic, bluish, and mauve colors found in some corals the coral makes itself.

Coral Diversity

In the and then-called true stony corals, which compose most tropical reefs, each polyp sits in a loving cup fabricated of calcium carbonate. Stony corals are the most of import reef builders, just organpipe corals, precious red corals, and bluish corals as well have stony skeletons. There are also corals that use more flexible materials or tiny stiff rods to build their skeletons—the seafans and sea rods, the rubbery soft corals, and the black corals.

The family tree of the animals nosotros call corals is complicated, and some groups are more closely related to each other than are others. All but the fire corals (named for their strong sting) are anthozoans, which are divided into ii main groups. The hexacorals (including the truthful stony corals and black corals, as well every bit the ocean anemones) accept smoothen tentacles, often in multiples of vi, and the octocorals (soft corals, seafans, organpipe corals and blue corals) have eight tentacles, each of which has tiny branches running along the sides. All corals are in the phylum Cnidaria, the aforementioned every bit jellyfish.

Reproduction

Corals have multiple reproductive strategies – they tin can exist male or female or both, and tin can reproduce either asexually or sexually. Asexual reproduction is important for increasing the size of the colony, and sexual reproduction increases genetic variety and starts new colonies that can be far from the parents.

ASEXUAL REPRODUCTION

Asexual reproduction results in polyps or colonies that are clones of each other - this can occur through either budding or fragmentation. Budding is when a coral polyp reaches a certain size and divides, producing a genetically identical new polyp. Corals do this throughout their lifetime. Sometimes a function of a colony breaks off and forms a new colony. This is called fragmentation, which can occur as a effect of a disturbance such equally a tempest or being striking by fishing equipment.

SEXUAL REPRODUCTION

In sexual reproduction, eggs are fertilized by sperm, unremarkably from another colony, and develop into a free-swimming larva. At that place are two types of sexual reproduction in corals, external and internal. Depending on the species and type of fertilization, the larvae settle on a suitable substrate and become polyps afterward a few days or weeks, although some can settle within a few hours!

Most stony corals are circulate spawners and fertilization occurs exterior the torso (external fertilization). Colonies release huge numbers of eggs and sperm that are often glued into bundles (one packet per polyp) that float towards the surface. Spawning often occurs just once a twelvemonth and in some places is synchronized for all individuals of the same species in an expanse. This blazon of mass spawning usually occurs at night and is quite a spectacle. Some corals brood their eggs in the body of the polyp and release sperm into the water. As the sperm sink, polyps containing eggs take them in and fertilization occurs inside the body (internal fertilization). Brooders often reproduce several times a twelvemonth on a lunar cycle.

From Corals to Reefs

Coral Growth

Individual coral polyps within a reef are typically very small—usually less than half an inch (or ~i.5 cm) in diameter. The largest polyps are institute in mushroom corals, which can exist more than 5 inches across. Merely because corals are colonial, the size of a colony tin be much larger: big mounds can be the size of a modest machine, and a single branching colony can cover an entire reef.

Reefs, which are usually made upward of many colonies, are much bigger however. The largest coral reef is the Great Barrier Reef, which spans one,600 miles (2,600 km) off the east coast of Australia. It is and then big that it can be seen from space!

Reefs form when corals grow in shallow water close to the shore of continents or smaller islands. The majority of coral reefs are called fringe reefs because they fringe the coastline of a nearby landmass. Only when a coral reef grows around a volcanic isle something interesting occurs. Over millions of years, the volcano gradually sinks, every bit the corals continue to abound, both upward towards the surface and out towards the open ocean. Over fourth dimension, a lagoon forms between the corals and the sinking island and a bulwark reef forms around the lagoon. Eventually, the volcano is completely submerged and just the ring of corals remains. This is called an atoll. Waves may eventually pile sand and coral debris on peak of the growing corals in the atoll, creating a strip of country. Many of the Marshall islands, a system of islands in the Pacific Ocean and home to the Marshallese, are atolls.

It takes a long time to abound a big coral colony or a coral reef, because each coral grows slowly. The fastest corals expand at more than 6 inches (15 cm) per year, just most grow less than an inch per year. Reefs themselves grow fifty-fifty more slowly considering afterward the corals dice, they break into smaller pieces and get compacted. Individual colonies can ofttimes live decades to centuries, and some deep-sea colonies have lived more than 4000 years. One way we know this is because corals lay down annual rings, only equally copse do. These skeletons can tell u.s.a. about what atmospheric condition were like hundreds or thousands of years ago. The Great Barrier Reef as information technology exists today began growing about 20,000 years ago.

Where are Reefs Found?

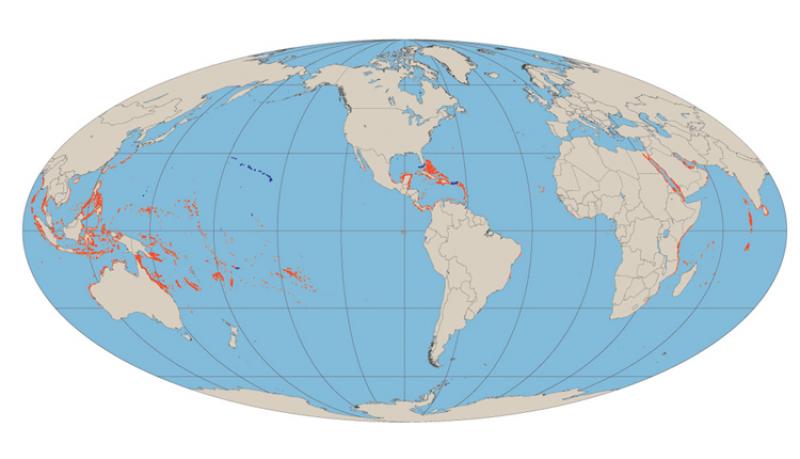

Corals are found across the world'due south ocean, in both shallow and deep water, merely reef-edifice corals are only found in shallow tropical and subtropical waters. This is because the algae found in their tissues need light for photosynthesis and they prefer water temperatures between lxx-85°F (22-29°C).

There are also deep-sea corals that thrive in cold, dark water at depths of upward to xx,000 feet (6,000 one thousand). Both stony corals and soft corals can be found in the deep sea. Deep-ocean corals practise not have the same algae and do not need sunlight or warm water to survive, but they also grow very slowly. One place to observe them is on underwater peaks called seamounts.

Reefs as Ecosystems

Cities of the Sea

Reefs are the large cities of the ocean. They exist because the growth of corals matches or exceeds the death of corals – think of it every bit a race between the construction cranes (new coral skeleton) and the wrecking assurance (the organisms that kill coral and chew their skeletons into sand).

When corals are babies floating in the plankton, they can exist eaten by many animals. They are less tasty once they settle down and secrete a skeleton, but some fish,worms, snails and sea stars casualty on developed corals.Crown-of-thorns sea stars are particularly voracious predators in many parts of the Pacific Ocean. Population explosions of these predators tin result in a reef being covered with tens of thousands of these starfish, with most of the coral killed in less than a year.

Corals as well have to worry about competitors. They use the same nematocysts that catch their food to sting other encroaching corals and keep them at bay. Seaweeds are a particularly unsafe competitor, as they typically grow much faster than corals and may contain nasty chemicals that injure the coral as well.

Corals do not take to only rely on themselves for their defenses considering mutualisms (beneficial relationships) grow on coral reefs. The partnership between corals and their zooxanthellae is one of many examples of symbiosis, where unlike species live together and aid each other. Some coral colonies have venereal and shrimps that live inside their branches and defend their home against coral predators with their pincers. Parrotfish, in their quest to find seaweed, will oftentimes bite off chunks of coral and will subsequently poop out the digested remains every bit sand.1 kind of goby chews upwardly a particularly nasty seaweed, and even benefits by becoming more poisonous itself.

Conservation

Threats

Global

The greatest threats to reefs are rising water temperatures and ocean acidification linked to rising carbon dioxide levels. High water temperatures cause corals to lose the microscopic algae that produce the nutrient corals demand—a condition known as coral bleaching. Severe or prolonged bleaching tin kill coral colonies or go out them vulnerable to other threats. Meanwhile, sea acidification means more acidic seawater, which makes information technology more difficult for corals to build their calcium carbonate skeletons. And if acidification gets severe enough, it could fifty-fifty suspension apart the existing skeletons that already provide the structure for reefs. Scientists predict that past 2085 ocean weather will be acidic enough for corals around the globe to brainstorm to deliquesce. For one reef in Hawaii this is already a reality.

Local

Unfortunately, warming and more acid seas are not the only threats to coral reefs. Overfishing and overharvesting of corals besides disrupt reef ecosystems. If care is not taken, boat anchors and divers can scar reefs. Invasive species tin also threaten coral reefs. The lionfish, native to Indo-Pacific waters, has a fast-growing population in waters of the Atlantic Ocean. With such large numbers the fish could greatly impact coral reef ecosystems through consumption of, and competition with, native coral reef animals.

Even activities that take place far from reefs can have an impact. Runoff from lawns, sewage, cities, and farms feeds algae that can overwhelm reefs. Deforestation hastens soil erosion, which clouds water—smothering corals.

Coral Bleaching

"Coral bleaching" occurs when coral polyps lose their symbiotic algae, the zooxanthellae. Without their zooxanthellae, the living tissues are nearly transparent, and you tin can see correct through to the stony skeleton, which is white, hence the name coral bleaching. Many different kinds of stressors can cause coral bleaching – water that is likewise common cold or besides hot, too much or besides little light, or the dilution of seawater by lots of fresh water can all cause coral bleaching. The biggest cause of bleaching today has been rising temperatures caused by global warming. Temperatures more than two degrees F (or 1 degree C) above the normal seasonal maximimum tin can cause bleaching. Bleached corals do not dice right away, just if temperatures are very hot or are too warm for a long time, corals either die from starvation or illness. In 1998, fourscore percent of the corals in the Indian Bounding main bleached and xx percentage died.

Protecting Coral Reefs

There is much that we can do locally to protect coral reefs, by making sure there is a salubrious fish community and that the water surrounding the reefs is clean. Well-protected reefs today typically have much healthier coral populations, and are more than resilient (better able to recover from natural disasters such as typhoons and hurricanes).

Fish play important roles on coral reefs, particularly the fish that eat seaweeds and keep them from smothering corals, which abound more slowly than the seaweeds. Fish likewise swallow the predators of corals, such as crown of thorns starfish. Marine protected areas (MPAs) are an of import tool for keeping reefs healthy. Big MPAs protect the Not bad Barrier Reef and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, for example, and in June 2012, Australia created the largest marine reserve network in the world. Smaller ones, managed past local communities, take been very successful in developing countries.

Clean water is too important. Erosion on country causes rivers to dump mud on reefs, smothering and killing corals. Seawater with too many nutrients speeds up the growth of seaweeds and increases the nutrient for predators of corals when they are developing every bit larvae in the plankton. Clean water depends on careful use of the land, avoiding as well many fertilizers and erosion caused by deforestation and certain construction practices. In the long run, however, the hereafter of coral reefs will depend on reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which is increasing rapidly due to called-for of fossil fuels. Carbon dioxide is both warming the ocean, resulting in coral bleaching, and changing the chemistry of the ocean, causing body of water acidification. Both making it harder for corals to build their skeletons.

Corals at the Smithsonian

Collections

The coral collection housed at the National Museum of Natural History may be the largest and best documented in the earth. Its jewel is a collection of shallow-water corals from the U.S. South Seas Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842—one of the largest voyages of discovery in the history of Western exploration. The expedition brought back many unknown specimens that scientists used to name and describe almost all Pacific reef corals. These are known equally type specimens in the collection. Birthday, the collection includes specimens of nigh four,820 species of corals, and about 65 percent of those species live in deep h2o.

Research

Carrie Bow Cay Field Station

In the late 1960s, several Smithsonian scientists set themselves an aggressive goal: understanding the inner workings of Caribbean area coral reefs. To study this complex ecosystem, they needed a field station where they could conduct inquiry in i location, from multiple disciplines, over a long period of time.

In 1972 they came across a tiny isle with three shuttered buildings. It was almost all the major habitats and isolated enough to permit study of the coral reef's natural dynamics. It was the perfect spot. More than three decades later on, Carrie Bow Cay in Belize is still dwelling to the Caribbean area Coral Reef Ecosystem Program. Scientists and students from around the world go along to survey the surface area's reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves; find new species; and pioneer new research techniques. Check out this video of Smithsonian scientists monitoring Acroporid populations near Carrie Bow.

The Artillery Project

It's not very colorful. And it's not made of coral. But by mimicking the nooks and crannies of real coral reefs, this Autonomous Reef Monitoring Construction (Artillery) attracts venereal, shrimps, worms, urchins, sponges, and many other kinds of marine invertebrates.

Researchers from the Census of Marine Life's CReefs Initiative set up upwardly these temporary plastic "flat houses" near coral reefs to learn more than about the diversity of reef species. They leave the structures underwater for near a twelvemonth. Then they retrieve the ARMS and clarify what life forms take taken up residence. CReefs researchers accept deployed hundreds of ARMS effectually the earth in places like Hawaii, Australia, Moorea, Taiwan, and Panama in lodge to compare biodiversity among unlike, and often distant, reefs.

Smithsonian Scientists

Dr. Nancy Knowlton

Coral reef biologist Dr. Nancy Knowlton is leading the Smithsonian's effort to increase public understanding of the world's ocean. She has studied the environmental and evolution of coral reefs for many years and is securely concerned nearly their time to come. "During the 3 decades I've been studying coral reefs in the Caribbean, we've lost 80% of the reefs there," she says. But she remains hopeful. "Y'all take to brand people realize that the situation is incredibly serious, just that there's something they can exercise."

Besides holding the Smithsonian's Sant Chair for Marine Science, Dr. Knowlton currently serves on the Pew Marine Fellows Advisory Commission, the Sloan Inquiry Fellowship in Ocean Sciences commission, and the national board the Coral Reef Alliance. She is an Aldo Leopold Leadership Beau, winner of the Peter Benchley Prize and the Heinz Award, and writer of Citizens of the Sea.

Dr. Stephen Cairns

When he was 10 years old, Stephen Cairns lived in Cuba and collected bounding main shells. That's when he decided to become a marine scientist. Today he is a enquiry zoologist at the Smithsonian'southward National Museum of Natural History, focusing on the diversity, distribution, and evolution of deep-water corals—both fossil and living. Deep-h2o corals live upward to 4 miles deep in cold, dark waters. Then Dr. Cairns conducts much of his field work on oceangoing inquiry vessels and in deep-sea submersibles. Dr. Cairns has published about 150 papers and books, in which he has described more 400 new species of deep-water corals. He assures us there are still many more to exist discovered.

Source: https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/invertebrates/corals-and-coral-reefs

0 Response to "The Coral Here She Comes Again"

Post a Comment